Big political ideas are rarely held in isolation. Before the internet, they were shared through mail, travelers and immigration. So discussion of who has a voice in government easily swept around the world in the late 19th and early 20th Century.

China, in the middle of profound political turmoil, was not immune. A fractured leadership was pulling the country in different directions. College students were returning from the US and other countries with new ideas. And students in China were becoming more outspoken. Some worked to shape a new Chinese model of government…and some to disseminate power to more people.

In 1919, multiple issues came together in student uprisings in Peking/Beijing. One of the students was a young woman, Edith E. Y. Wang. Here is her perspective, written in c. 1922 while in Chicago for college:

Now I want to tell you about my experience during the earlier part of women’s movement. The year of 1919 was my last year in [Tienstin] Girls Normal School. We, several of my classmates and I, did not know what we should do after we graduated.

Of course at that time to be a teacher or to be married is the only way for us. There was no college or any other chance for women to get a higher education than normal training except to be abroad. [Ginling] College and Union Women’s College, which are missionary institutions, are not much higher than a normal school. Therefor we organized a society to discuss our study problems.

A few months after the ‘Students’ Movement’ had been started at Peping, the Peking National University was the [beginning]. One of the University student was killed. Then we decided to have a funeral meeting for him in which we gave several speeches about the recent politic condition and the government. The Women’s teachers, students, and some other well educated young ladies were invited.

After that meeting a business meeting was held. Fortunately all of our guests volunteerly joined this organization. We named it “The United Women’s Association.” It is three years old now and still doing very [progressively] and successfully. The most import work is to help those women who have no chance to be educated. Because our fundamental propose is to make the woman be a good citizen.

When the fall I was a student at [Ginling] College. I could learn nothing but English Language. Many of the professors at Peking National University have been very active and broad minded and numbers of students too. Mr. Kang and Mr. Wong were the important ones. So the University is known by the name of a center of new civilization. That made us to ask the equal rights in the University first.

The beginning we wrote a letter to the university saying: “as this university is a most liberal institution which is known by the nation, the nation as a whole including both men and women, not one sided. Is that justice that you only give the opportunity to the men? We need higher education but there is no chance for us. You ought to show the light of liberty and freedom, and let it shine the darkness in the world. You have the ability. It is no use of saying or writing, but do it!”

One of the proffers answered: “There is no lady knock the door that is why the door is still close. If there is anyone knocking it we shall wide open it for her.” The president, Mr. Chai, said: “There is no such law that woman is no allowed to be in this university. Of course we have not had any woman student here since this institution started, but it is only a custom, a custom is easily to be [moved?]”

Since then I was going there, but the difficulty was my father not allowed to. Consequently I thought in [Tienstin] to [meet] my chance came…Fortunately after summer father led me go. I had a happiest time in my work for a whole year until the teachers’ strike which made the school closed for nearly half year. So left my lovely country and came here.

I wish that I only could have a chance to stay one more year in this country, but I know it is only a dream.

When she wrote this letter, Edith was attending the University of Chicago. Unfortunately, her wealthy but conservative family was not nearly as supportive as the University. Her father paid for her to start studying, but then cut her off in an effort to get her home. She obtained work as a housekeeper and nanny to a boy named Lincoln, with a family that travelled first to Berlin and planned to go on to China.

As Edith noted from Berlin in relation to her own education: “For it is really a tragedy that an ambitious young person to lose her energy and light. For the humanity sake we have to fight for it. Is it so?”

Regrettably, I have no further information on Ms. Wang and her destiny. My research, limited by language, has found no trace. She may have changed her name, since her employers knew her as Ms. Ling.

Edith Wang was returning to turmoil in China, c. 1923. Political factions fighting for control would shortly be fighting even more actively against Japanese military aggression. My hope is that she survived and kept her focus on education and on empowering women. What a great legacy!

A few years later, in 1926, Elizabeth discussed women’s rights with a small group of University women in Peking/Beijing. She reported this on their conversation:

“…[O]nce the kind of government they are working for can be achieved, [they agreed] woman equality before the law will be practically an automatic thing. They say that the few women who spend all their activities at this chaotic time in agitating for the suffrage are considered rather foolish and not taken very seriously. For where is the power that could grant them suffrage, even if so disposed? Also, I learn, that the two chief woman leaders for suffrage have lost favor by dividing their forces and indulging in private personal quarrels publicly in the newspapers, and in joining the more radical wing of the Kuomintang.”

So an expectation of women’s rights for these young college women. But a skeptical eye on fighting for suffrage when they didn’t yet know the final form of government.

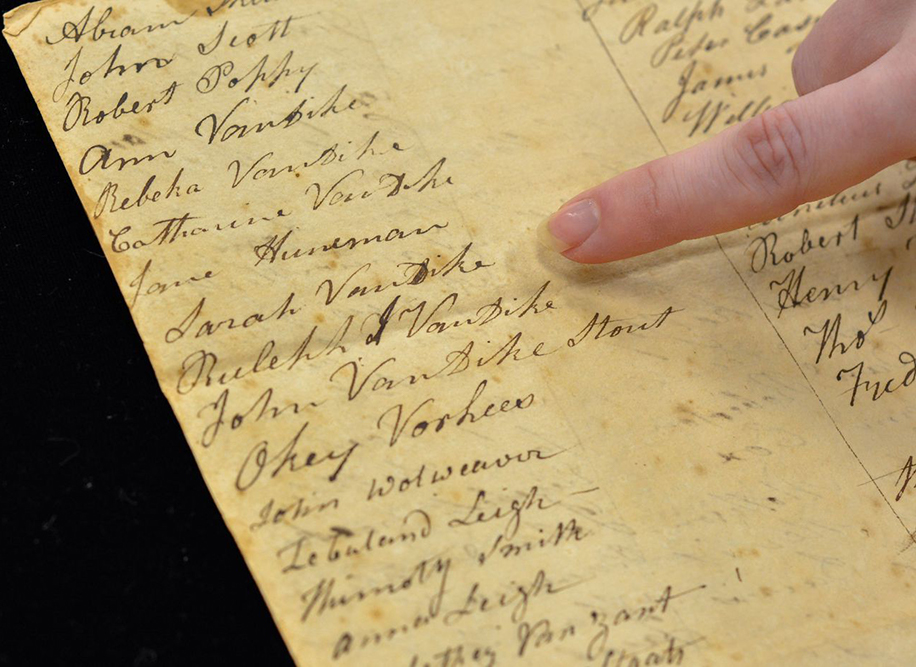

Image: 1926 Student Protest, Beijing. Letters quoted and image are property of the author.

Shirley Marshall, A Radical Suffragist.

Leave a comment